Beyond Bore Axis: Handgun Recoil Characteristics and Lowering Felt Recoil

Two of the pistols sent to us for review and testing, a Steyr L9-A1 and a Tristar P-120, seemed like a good pairing for a “quick” discussion of the intricacies of handgun recoil before they disappeared back into their boxes to return to the manufacturer.

Left: Steyr L9-A1 Right: Tristar P-120 (Turkish CZ SP-01 clone)

The Steyr L9-A1 and the Tristar P-120 are both 9mm ‘duty’ pistols – big frames, ~4.5” barrels, and plenty of space for a light under the barrel. Outside of that, these two might not seem like the most obvious candidates for comparison, but in actuality, they both commit hard to reducing muzzle flip as much as possible. However, they go about this task in completely different ways.

The Steyr is very nouveau – it went striker-fired to get the bore as low as possible. An unusually steep grip angle helps, too.

The Tristar, on the other hand, opts for a very old-school approach - use a gigantic all-steel frame to soak up recoil, internal frame rails to get the bore as low as possible, and make it hammer-fired because, well, back then almost everything was hammer-fired. The "back then" is the 70s when the CZ-75 was born - the Tristar P-120 is a Turkish copy of a CZ SP-01. It’s worth noting that while the P-120 has a low bore axis relative to other hammer guns, it’s still quite high compared to striker guns like the Steyr.

When we fired the two pistols back-to-back, using the same ammunition, the difference in felt recoil was conclusive - the Tristar P-120 (CZ SP-01) kicked less. There is a notion that bore axis is the critical puzzle piece regarding recoil reduction in handguns, but while bore axis is important, it's not the whole picture. Assuming all your options are chambered in the same cartridge, recoil in a semi-automatic handgun is actually composed of four principle factors, bore axis height being only one of them. Here they are in no particular order:

Factor #1: Non-reciprocating Mass

Non-reciprocating mass means any part of the handgun that doesn't get actuated during recoil, so: the frame, the grips, the guiderod (only if it's a full-length guide rod - short guiderods move with the slide and so should be counted as reciprocating mass), and pretty much anything else that isn't part of the upper half. The heavier these parts of the gun are, the more recoil will be absorbed by the gun itself without being felt by the shooter, which is why purposefully heavy parts like tungsten guiderods and weighted grip panels exist.

The Steyr is very nouveau – it went striker-fired to get the bore as low as possible. An unusually steep grip angle helps, too.

The Tristar, on the other hand, opts for a very old-school approach - use a gigantic all-steel frame to soak up recoil, internal frame rails to get the bore as low as possible, and make it hammer-fired because, well, back then almost everything was hammer-fired. The "back then" is the 70s when the CZ-75 was born - the Tristar P-120 is a Turkish copy of a CZ SP-01. It’s worth noting that while the P-120 has a low bore axis relative to other hammer guns, it’s still quite high compared to striker guns like the Steyr.

When we fired the two pistols back-to-back, using the same ammunition, the difference in felt recoil was conclusive - the Tristar P-120 (CZ SP-01) kicked less. There is a notion that bore axis is the critical puzzle piece regarding recoil reduction in handguns, but while bore axis is important, it's not the whole picture. Assuming all your options are chambered in the same cartridge, recoil in a semi-automatic handgun is actually composed of four principle factors, bore axis height being only one of them. Here they are in no particular order:

Factor #1: Non-reciprocating Mass

Non-reciprocating mass means any part of the handgun that doesn't get actuated during recoil, so: the frame, the grips, the guiderod (only if it's a full-length guide rod - short guiderods move with the slide and so should be counted as reciprocating mass), and pretty much anything else that isn't part of the upper half. The heavier these parts of the gun are, the more recoil will be absorbed by the gun itself without being felt by the shooter, which is why purposefully heavy parts like tungsten guiderods and weighted grip panels exist.

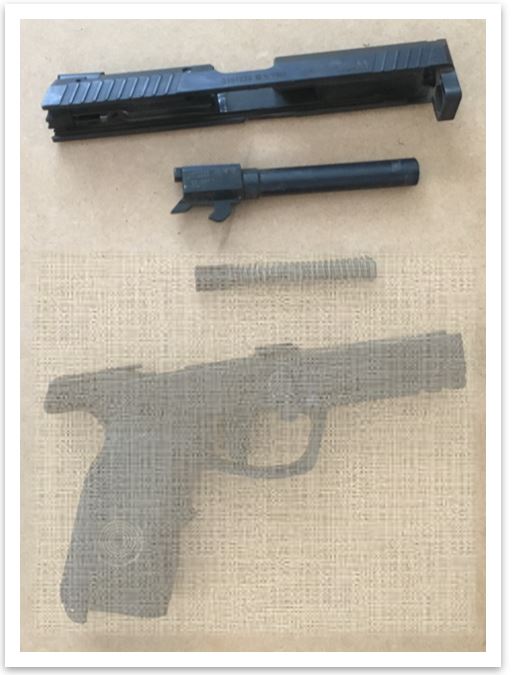

The un-blurred components make up a typical handgun’s non-reciprocating mass.

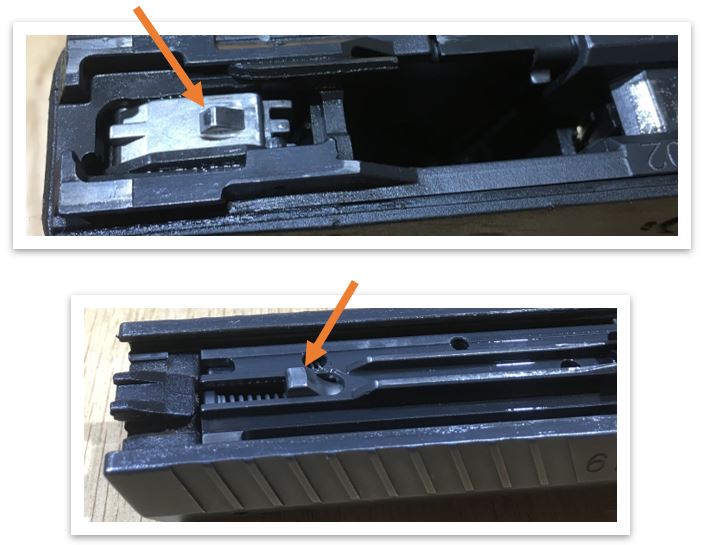

On this Steyr, the full-length guiderod and spring counts as non-reciprocating mass

On this Steyr, the full-length guiderod and spring counts as non-reciprocating mass

However, the simplest way to get big numbers for non-reciprocating mass is to start with a handgun that has a full-size steel frame - loaded, the Tristar P-120 weighs a whopping 3.1 lbs, over a full pound heavier than a comparably-sized polymer-frame pistol. This weight reduces muzzle jump dramatically, permitting faster follow-up shots and generally making the shooting experience more pleasant, especially with authoritative rounds like .45 ACP. The tradeoff is simply weight - a heavier gun is less comfortable on the hip and some would argue, slower to bring to aim and swing between targets.

So how does this concept play out in the Steyr and the Tristar CZ clone? Well, the non-reciprocating mass of the P-120 is 22.6 oz, more than double the Steyr's non-reciprocating mass of 9.0 oz. Small wonder that the P-120 kicked less.

So how does this concept play out in the Steyr and the Tristar CZ clone? Well, the non-reciprocating mass of the P-120 is 22.6 oz, more than double the Steyr's non-reciprocating mass of 9.0 oz. Small wonder that the P-120 kicked less.

|

Factor #2: Reciprocating Mass

Reciprocating mass means any part of the handgun that does get actuated during recoil, so: the slide, the barrel, the guiderod (only if it's a short guide rod - full-length guiderods do not move with the slide and so should be counted as non-reciprocating mass), the extractor, sights, and pretty much anything else that isn't part of the lower half. The lighter these parts are, the less momentum they will generate when they snap backward as the slide opens after firing, which is why many competition-oriented pistols have windows or other lightening cuts in their slide. |

Note that porting a slide is not the same as a lightening cut, even though the ports do lighten the slide a little. A ported slide is intended to be matched with a ported barrel, which reduces recoil by replicating the effect of a muzzle brake.

|

The un-blurred components make up a typical handgun’s reciprocating mass.

On this Steyr, the full-length guiderod and spring counts as non-reciprocating mass

On this Steyr, the full-length guiderod and spring counts as non-reciprocating mass

The tradeoff in drilling holes or making cuts to your slide is reduced reliability, which occurs due to two reasons:

Reason 1 is obvious: turning your slide into swiss cheese is practically an invitation for dust and grit to get inside and jam up your pistol's deepest internal workings.

Reason 2: a lighter slide has less momentum, which makes it easier to get stopped in its tracks (literally) by debris in the frame rails or a tough-to-extract casing. For a relevant example, look to the massively reliable and just plain massive long-stroke AK-pattern rifle's bolt group - the entire mammoth hunk of metal moves as one unit from start to finish, so once that bolt group gets to movin' backward, there is very little that can stop it before it bottoms out at the back of the AK's receiver.

Reciprocating mass varies widely, but modern pistols tend to be heavier up top than older designs due to the current habit of machining slides cheaply from square tube stock, eschewing the more contoured slides common to many older hammer guns. For example, the boxily-machined Glock 17 has a fairly weighty reciprocating mass of 16.8 oz, while a Norinco Type 54-1 in 9mm (a Tokarev TT clone and good example of an old-school 9mm hammer gun with a similar barrel length) easily bests the Glock, the Steyr, and the Tristar/CZ with a reciprocating mass of 13.4 oz, more than 3 full oz lighter than the Glock. Of course, a Beretta 92’s minimalist slide beats them all.

So how does this concept play out in the Steyr and the Tristar CZ clone? Well, the Steyr's reciprocating mass just slightly takes the win - 15.4 oz versus the P-120's 15.8 oz. This difference in slide weight isn't eye-popping, but bear in mind that even a small difference in weight is magnified when the slide is zooming backward at umpteen miles per hour.

Factor #3: Recoil Spring Stiffness

There are two stages to a semi-automatic pistol's recoil.

Stage 1: the slide shoots backward and bottoms out against the rear frame stop, transferring momentum to the shooter's hand and (typically) kicking the muzzle upward.

Stage 2: the slide rockets forward and bottoms out against the front frame stop, transferring momentum to the frame of the gun and (typically) kicking the muzzle downward.

A stiffer recoil spring will decrease the recoil generated during stage 1, because a stiffer spring will absorb more of the slide's energy. However, that same stiff recoil spring will also increase recoil by snapping the slide closed energetically, which makes the gun nosedive and throws off sight alignment. Weaker springs demonstrate the opposite behavior - recoil is increased during stage 1 and decreased during stage 2. All this is proven out under scrutiny with high-speed camera footage - a pistol with a weaker spring has a much faster opening stroke, and a much slower closing stroke.

For what it's worth, lighter springs are generally favored for competition alongside low-powered ammunition (where permitted) - the mild ammo reduces upward muzzle flip during stage 1, while the weak spring reduces downward muzzle flip during stage 2. A weaker spring also increases the total cycle time of a given load by 10-20% (even though it actually shortens the travel time of the opening stroke), and extending the total elapsed time of an impact event is the best way to reduce a felt impact overall - virtually all recoil absorbers, from spring-operated gas cylinders in the stock to plain old rubber buttpads, operate by compressing under recoil and thus spreading the impact out over a few extra milliseconds.

It's tough to compare spring strength, but as a rule, hammer guns can get away with weaker action springs than striker guns for two reasons:

1) the hammer adds drag to the opening stroke of the action, slowing it down as the hammer is cocked, so you can use a slightly weaker spring and still keep the slide at a healthy velocity

2) like the striker in the Steyr, most striker pistols cock the striker on the closing stroke of the slide, so they need a stiffer spring to give enough energy to strip a round from the mag, fully cock the striker, and then fully close the breech. However, a few striker guns such as the Glock, S&W SD, and Ruger SR9 rely (partially) on trigger pull to cock back the striker, and so they can use a slightly weaker action spring.

Reason 1 is obvious: turning your slide into swiss cheese is practically an invitation for dust and grit to get inside and jam up your pistol's deepest internal workings.

Reason 2: a lighter slide has less momentum, which makes it easier to get stopped in its tracks (literally) by debris in the frame rails or a tough-to-extract casing. For a relevant example, look to the massively reliable and just plain massive long-stroke AK-pattern rifle's bolt group - the entire mammoth hunk of metal moves as one unit from start to finish, so once that bolt group gets to movin' backward, there is very little that can stop it before it bottoms out at the back of the AK's receiver.

Reciprocating mass varies widely, but modern pistols tend to be heavier up top than older designs due to the current habit of machining slides cheaply from square tube stock, eschewing the more contoured slides common to many older hammer guns. For example, the boxily-machined Glock 17 has a fairly weighty reciprocating mass of 16.8 oz, while a Norinco Type 54-1 in 9mm (a Tokarev TT clone and good example of an old-school 9mm hammer gun with a similar barrel length) easily bests the Glock, the Steyr, and the Tristar/CZ with a reciprocating mass of 13.4 oz, more than 3 full oz lighter than the Glock. Of course, a Beretta 92’s minimalist slide beats them all.

So how does this concept play out in the Steyr and the Tristar CZ clone? Well, the Steyr's reciprocating mass just slightly takes the win - 15.4 oz versus the P-120's 15.8 oz. This difference in slide weight isn't eye-popping, but bear in mind that even a small difference in weight is magnified when the slide is zooming backward at umpteen miles per hour.

Factor #3: Recoil Spring Stiffness

There are two stages to a semi-automatic pistol's recoil.

Stage 1: the slide shoots backward and bottoms out against the rear frame stop, transferring momentum to the shooter's hand and (typically) kicking the muzzle upward.

Stage 2: the slide rockets forward and bottoms out against the front frame stop, transferring momentum to the frame of the gun and (typically) kicking the muzzle downward.

A stiffer recoil spring will decrease the recoil generated during stage 1, because a stiffer spring will absorb more of the slide's energy. However, that same stiff recoil spring will also increase recoil by snapping the slide closed energetically, which makes the gun nosedive and throws off sight alignment. Weaker springs demonstrate the opposite behavior - recoil is increased during stage 1 and decreased during stage 2. All this is proven out under scrutiny with high-speed camera footage - a pistol with a weaker spring has a much faster opening stroke, and a much slower closing stroke.

For what it's worth, lighter springs are generally favored for competition alongside low-powered ammunition (where permitted) - the mild ammo reduces upward muzzle flip during stage 1, while the weak spring reduces downward muzzle flip during stage 2. A weaker spring also increases the total cycle time of a given load by 10-20% (even though it actually shortens the travel time of the opening stroke), and extending the total elapsed time of an impact event is the best way to reduce a felt impact overall - virtually all recoil absorbers, from spring-operated gas cylinders in the stock to plain old rubber buttpads, operate by compressing under recoil and thus spreading the impact out over a few extra milliseconds.

It's tough to compare spring strength, but as a rule, hammer guns can get away with weaker action springs than striker guns for two reasons:

1) the hammer adds drag to the opening stroke of the action, slowing it down as the hammer is cocked, so you can use a slightly weaker spring and still keep the slide at a healthy velocity

2) like the striker in the Steyr, most striker pistols cock the striker on the closing stroke of the slide, so they need a stiffer spring to give enough energy to strip a round from the mag, fully cock the striker, and then fully close the breech. However, a few striker guns such as the Glock, S&W SD, and Ruger SR9 rely (partially) on trigger pull to cock back the striker, and so they can use a slightly weaker action spring.

Although the Steyr’s striker and sear are steeply angled (which gives a light, crisp trigger pull),

they are still SAO and thus add extra load on the recoil spring as the slide closes.

they are still SAO and thus add extra load on the recoil spring as the slide closes.

Factor #4: Bore Axis Height

When a handgun recoils, the higher the barrel and slide sit above your hand, the more leverage they have and the harder it is to control muzzle flip. Pistol designs that sit the barrel and slide as low above your grip as possible reduce that leverage, and make recoil easier to control. This factor is complicated enough to warrant its own article: Bore Axis Comparison.

Closing Comments

Finally, there is the question of whether the flex in a polymer-framed handguns frame absorbs recoil. Frankly, we don’t have the data to prove or disprove this notion, but our educated guess is that it’s nonsense. Unless the frame was made of rubber, like a recoil pad, it’s not going to flex enough to absorb an appreciable amount of energy (although it will flex enough to prevent stress cracking, which is why polymer frames tend to outlive aluminum or steel frames).

So back to our two candidates – the Steyr L9 and the Tristar P-120. Two very different approaches to reducing recoil, but only one can win: in this case, the P-120 (CZ SP-01).

The P-120 just kicks less – no question about it. That said, if you’re looking for a modern, polymer-framed striker gun, it’s worth considering how the different designs on the market approach the above 4 factors in order to choose the model with the softest recoil. The Steyr did what it could with a polymer frame, and it worked – it does kick less than a Glock we shot at the same time, even if it still can’t match the P-120. Additionally, polymer-framed strikers have a whole host of advantages over metal-framed hammer guns, no matter how much snappier they are to shoot, so there’s no simple “this type is better”. In the end, it's up to you the consumer to decide what you like best.

Happy shooting.

When a handgun recoils, the higher the barrel and slide sit above your hand, the more leverage they have and the harder it is to control muzzle flip. Pistol designs that sit the barrel and slide as low above your grip as possible reduce that leverage, and make recoil easier to control. This factor is complicated enough to warrant its own article: Bore Axis Comparison.

Closing Comments

Finally, there is the question of whether the flex in a polymer-framed handguns frame absorbs recoil. Frankly, we don’t have the data to prove or disprove this notion, but our educated guess is that it’s nonsense. Unless the frame was made of rubber, like a recoil pad, it’s not going to flex enough to absorb an appreciable amount of energy (although it will flex enough to prevent stress cracking, which is why polymer frames tend to outlive aluminum or steel frames).

So back to our two candidates – the Steyr L9 and the Tristar P-120. Two very different approaches to reducing recoil, but only one can win: in this case, the P-120 (CZ SP-01).

The P-120 just kicks less – no question about it. That said, if you’re looking for a modern, polymer-framed striker gun, it’s worth considering how the different designs on the market approach the above 4 factors in order to choose the model with the softest recoil. The Steyr did what it could with a polymer frame, and it worked – it does kick less than a Glock we shot at the same time, even if it still can’t match the P-120. Additionally, polymer-framed strikers have a whole host of advantages over metal-framed hammer guns, no matter how much snappier they are to shoot, so there’s no simple “this type is better”. In the end, it's up to you the consumer to decide what you like best.

Happy shooting.

From left: Norinco Type 54-1, Tristar P-120, Steyr L9-A1, Glock 17

Four 9mm duty guns with similar barrel lengths, but each with a very different design.

Four 9mm duty guns with similar barrel lengths, but each with a very different design.