Tulammo Steel-cased Ammo Accuracy Test: 55 gr, 62 gr, and 75 gr

|

The popular assumption is that steel-cased ammunition is less accurate than brass-cased ammunition. This is typically true, but it's more of a correlation than a causation. Highly accurate steel-cased ammunition does exist, such as Hornady's Steel Match line, so rather than getting hung up on case material, it's more correct to say that cheap ammunition is less accurate than expensive ammunition. Since steel-cased ammunition is almost universally cheap, it is almost universally pretty inaccurate, too.

|

Cost differences aside, it's fair to note that brass is a superior case material overall. It doesn't rust and it's lighter, more malleable, and slicker than steel.

|

But just how inaccurate? We've seen lots of opinions, but little data, and we especially wanted to see steel-cased ammunition given a fair trial by matching the bullet grain weight to the twist rate of the barrel. We decided to do a little testing and shoot some steel-cased ammo from a fully-supported bench position, but also give the ammo a chance to shine by matching grain weight to twist rate. Many ARs use 1:7 barrels these days (including the test rifle) so we needed heavy bullets, and as of this writing (Q3 2017) Tulammo's 75 grain .223 is the only cheap, steel-cased .223 above 62 grains, so we procured some of that, plus some Tulammo 62 grain and 55 grain for comparison.

|

All three Tulammo variants can be found for $4-$7 dollars per box of 20. We stayed with Tulammo to keep things consistent (if not exactly scientific), and also threw in a box of Federal Lake City 77-grain OTM (Open Tip Match). Coming in at about $18 per box of 20 and with a heavy bullet to boot, we expected the OTM to act as a high-accuracy control.

|

All the Tulammo variants used hollow point bullets, which were comparably priced to FMJ.

|

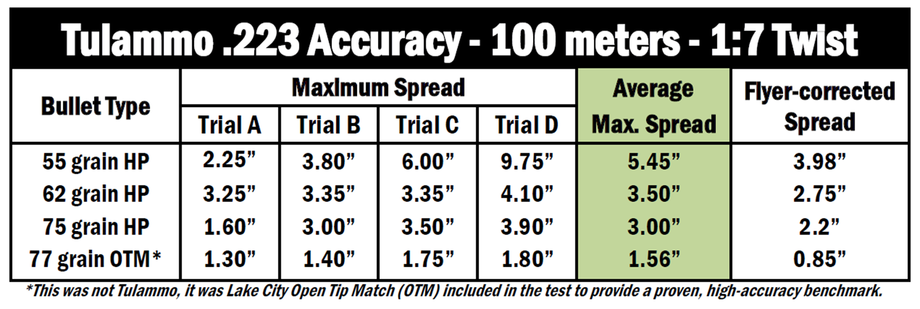

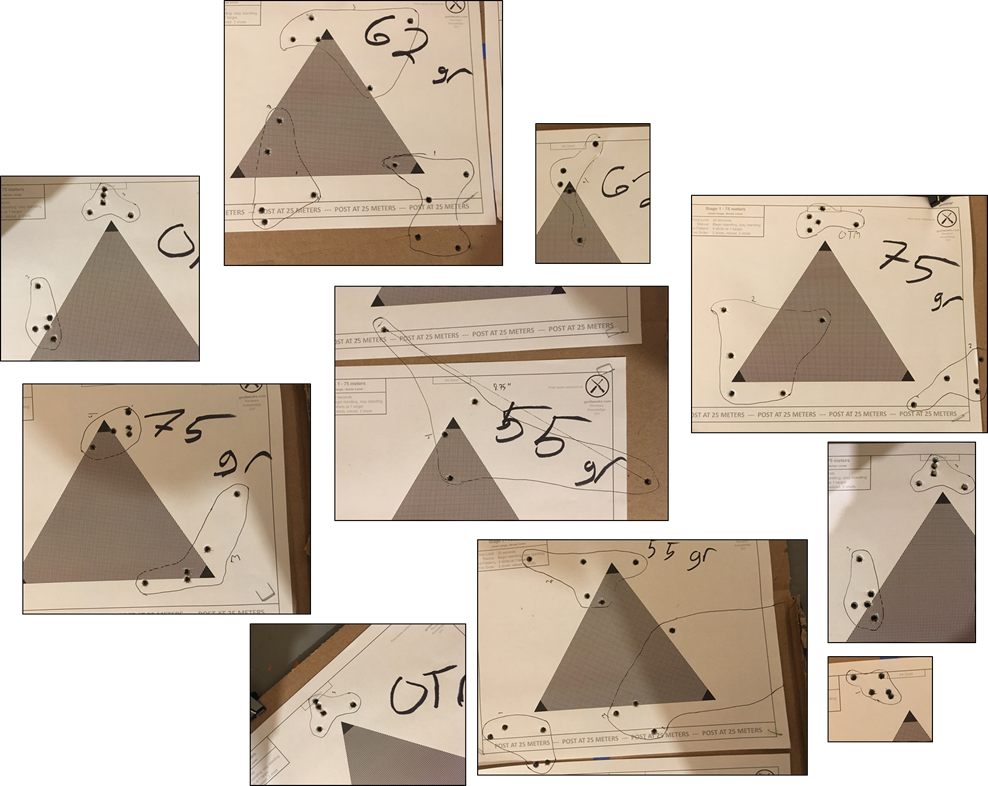

The chart below shows the results. We encourage you to read on below the chart for an explanation of the flyer-corrected spread, details on the test rifle and test setup, and more, but the TL;DR is as follows:

The 55 grain rounds started strong with a tidy 2.25" group, but as the barrel heated up, some truly horrifying groups emerged, maxing out at nearly 10.0 inches. Yes, 10 inches at 100 yards. Yikes... very yikes...

The 62 grain was pretty good, but not as good as the 75 grain, which started off with a particularly slick 1.6" group and managed to keep it under 4.0" overall - not bad for ammo that can be had for 15 cents per round.

The Federal OTM was serious as a heart attack, refusing to go above 1.80" even when the barrel was sizzling. What's more, according to the flyer-corrected score, it was actually shooting under 1 MOA the entire time.

The 55 grain rounds started strong with a tidy 2.25" group, but as the barrel heated up, some truly horrifying groups emerged, maxing out at nearly 10.0 inches. Yes, 10 inches at 100 yards. Yikes... very yikes...

The 62 grain was pretty good, but not as good as the 75 grain, which started off with a particularly slick 1.6" group and managed to keep it under 4.0" overall - not bad for ammo that can be had for 15 cents per round.

The Federal OTM was serious as a heart attack, refusing to go above 1.80" even when the barrel was sizzling. What's more, according to the flyer-corrected score, it was actually shooting under 1 MOA the entire time.

Maximum spread was measured center-to-center between the two shots furthest apart in a given 5-shot group.

|

Enjoying this article so far? Check us out on twitter!

|

Flyer-corrected Spread

Some of the groups had obvious flyers, particularly the 77 gr OTM. Given the test variables discussed below (floppy target backerboard, cheap scope rings, sun glare) it seemed likely that at least some of these flyers were induced by the equipment, shooter, or environment, and not by the ammunition itself. As a result, we calculated a secondary score that eliminated the worst flyers from the data. This "flyer-corrected" score is shown in the above chart, and while it is not as empirical as the raw score shown in green, it is worth considering both scores when thinking about the actual accuracy offered by the tested ammunition types.

Some of the groups had obvious flyers, particularly the 77 gr OTM. Given the test variables discussed below (floppy target backerboard, cheap scope rings, sun glare) it seemed likely that at least some of these flyers were induced by the equipment, shooter, or environment, and not by the ammunition itself. As a result, we calculated a secondary score that eliminated the worst flyers from the data. This "flyer-corrected" score is shown in the above chart, and while it is not as empirical as the raw score shown in green, it is worth considering both scores when thinking about the actual accuracy offered by the tested ammunition types.

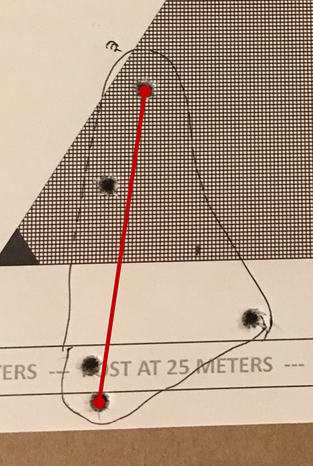

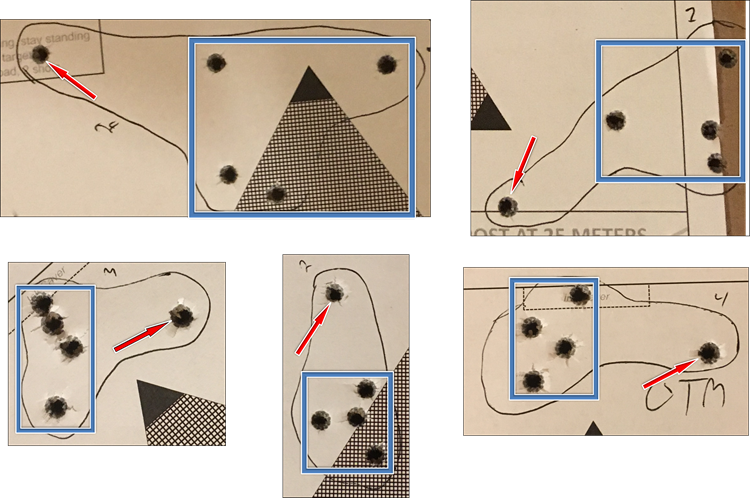

The above groups contain examples of what we consider to be flyers; four relatively close shots (highlighted by a blue box above) and one outlier.

Test Setup

The barrel used in this test was a Ballistic Advantage (BA) Modern series (QPQ, government profile) with a mid-length gas system and 1:7 twist. The Modern series is BA's cheapest barrel at about $160 for a stripped unit. It was broken in with 1 shot-1 clean for 5 shots, 3 shots-1 clean for 15 shots, and 5-shots 1 clean for 20 shots (40-shot break-in). Post break-in, this particular barrel has seen only a few hundred rounds of mixed steel- and brass-cased ammunition.

The rifle was a Fightlite SCR with a "parts" upper. The gas block is a shaved F-marked FSB, drilled/tapped to add set screws (not pinned), and tap-fit onto the shoulder with a hammer. The handguard is free-floating with the barrel nut torqued to 35 ft-lbs.

The scope was a Mueller APT 4.5-14x, a budget scope that has nonetheless proven quite capable in low-recoil applications over five or six years of use, and was picked for this test to take advantage of its high magnification and adjustable parallax correction. The Mueller originally sat in a sturdy set of all-steel rings with a true Picatinny crossbar, but these rings couldn't sit the scope high enough above the SCR's free float rail. A set of inexpensive UTG rings were the only rings close at hand that could sit the scope high enough, so on they went. The UTG rings were a lever-operated QD variety, which seemed like a particularly optimistic trait given their cost of ~$25 dollars, but they didn't have any obvious failures during the shoot.

The rifle was set up on rice-filled shooting bags, front and rear. Brown rice was chosen over white rice to ensure the rifle had adequate access to fiber and micronutrients. A quick and dirty comb riser was made from foam pipe insulation and electrical tape to support the taller optic mount.

The barrel used in this test was a Ballistic Advantage (BA) Modern series (QPQ, government profile) with a mid-length gas system and 1:7 twist. The Modern series is BA's cheapest barrel at about $160 for a stripped unit. It was broken in with 1 shot-1 clean for 5 shots, 3 shots-1 clean for 15 shots, and 5-shots 1 clean for 20 shots (40-shot break-in). Post break-in, this particular barrel has seen only a few hundred rounds of mixed steel- and brass-cased ammunition.

The rifle was a Fightlite SCR with a "parts" upper. The gas block is a shaved F-marked FSB, drilled/tapped to add set screws (not pinned), and tap-fit onto the shoulder with a hammer. The handguard is free-floating with the barrel nut torqued to 35 ft-lbs.

The scope was a Mueller APT 4.5-14x, a budget scope that has nonetheless proven quite capable in low-recoil applications over five or six years of use, and was picked for this test to take advantage of its high magnification and adjustable parallax correction. The Mueller originally sat in a sturdy set of all-steel rings with a true Picatinny crossbar, but these rings couldn't sit the scope high enough above the SCR's free float rail. A set of inexpensive UTG rings were the only rings close at hand that could sit the scope high enough, so on they went. The UTG rings were a lever-operated QD variety, which seemed like a particularly optimistic trait given their cost of ~$25 dollars, but they didn't have any obvious failures during the shoot.

The rifle was set up on rice-filled shooting bags, front and rear. Brown rice was chosen over white rice to ensure the rifle had adequate access to fiber and micronutrients. A quick and dirty comb riser was made from foam pipe insulation and electrical tape to support the taller optic mount.

Test Variables and Limitations

Target stand and targets:

The target stand was a free-hanging design where the backer board (a cardboard sheet) is clipped to the top crossbar only, allowing the backer board to swing freely in the breeze. This allows the target stand to be lightweight without tipping over in high winds, with the drawback that on windy days, you sometimes have to wait for the target to stand still. For this test, however, the bottom of the backer board was taped to the target stand's poles, which settled down wind-induced movement of the targets considerably, but did not eliminate it.

Target stand and targets:

The target stand was a free-hanging design where the backer board (a cardboard sheet) is clipped to the top crossbar only, allowing the backer board to swing freely in the breeze. This allows the target stand to be lightweight without tipping over in high winds, with the drawback that on windy days, you sometimes have to wait for the target to stand still. For this test, however, the bottom of the backer board was taped to the target stand's poles, which settled down wind-induced movement of the targets considerably, but did not eliminate it.

Shooting conditions:

The shoot took place in the late afternoon of a chilly, blustery day. Sun glare was a pronounced problem from the start, as the shooting bench was right in the path of slanting, late-afternoon rays, while the target was heavily shaded. The Ink Saver version of the GunTweaks CHCOF target was used, which performed acceptably in the dim lighting, but did not provide as much contrast as other versions of the CHCOF targets. See images below.

The shoot took place in the late afternoon of a chilly, blustery day. Sun glare was a pronounced problem from the start, as the shooting bench was right in the path of slanting, late-afternoon rays, while the target was heavily shaded. The Ink Saver version of the GunTweaks CHCOF target was used, which performed acceptably in the dim lighting, but did not provide as much contrast as other versions of the CHCOF targets. See images below.

Shooting conditions were acceptable but not optimal; note the heavily shaded target and the sun glare in the upper right.

Shot count:

It was a cold day and shots were fired at a measured pace, but with 80 rounds on the table plus zeroing shots, the barrel did start to heat up. However, since the shooting order was randomized, this affected all rounds consistently.

Fouled barrel:

The barrel had seen about 150 rounds since its last cleaning, and the bore was not cleaned before or during the test in order to demonstrate the practical results one could expect from a warm gun with a smutty barrel, albeit fired from a well-supported position.

It was a cold day and shots were fired at a measured pace, but with 80 rounds on the table plus zeroing shots, the barrel did start to heat up. However, since the shooting order was randomized, this affected all rounds consistently.

Fouled barrel:

The barrel had seen about 150 rounds since its last cleaning, and the bore was not cleaned before or during the test in order to demonstrate the practical results one could expect from a warm gun with a smutty barrel, albeit fired from a well-supported position.

Test Process

Each 20-rd box of ammunition was broken down into four 5-round strings. 80 rounds were used, so this produced 16 different 5-shot "samples". Each 5-shot sample was assigned to a paper slip which was dropped into the pocket of a range bag, then the slips were pulled at random and and fired. This was to ensure that no particular 5-shot sample would have a consistently cleaner or dirtier bore left from the previous string, since the Federal OTM was likely to leave a cleaner bore than the Tulammo.

GunTweaks CHCOF targets were used, so each sheet provided three pinpoint-accurate targets, one at each corner of the triangle. Since there were four samples per ammunition type, this necessitated two sheets per type; three targets on the first sheet and one target on the second sheet.

Each 20-rd box of ammunition was broken down into four 5-round strings. 80 rounds were used, so this produced 16 different 5-shot "samples". Each 5-shot sample was assigned to a paper slip which was dropped into the pocket of a range bag, then the slips were pulled at random and and fired. This was to ensure that no particular 5-shot sample would have a consistently cleaner or dirtier bore left from the previous string, since the Federal OTM was likely to leave a cleaner bore than the Tulammo.

GunTweaks CHCOF targets were used, so each sheet provided three pinpoint-accurate targets, one at each corner of the triangle. Since there were four samples per ammunition type, this necessitated two sheets per type; three targets on the first sheet and one target on the second sheet.

|

Test Results

As expected, the heavier bullets shot better out the 1:7 twist barrel. The progression was more or less linear: the 55 grain shot the worst groups, the 62 grain was a little better, the 75 grain was better still. Of course, the 77 grain OTM blew everything else away, but it also costs almost 3x more than the Tulammo. The 55 grain shot groups that were, in our view, unacceptably poor at around 5.5 MOA. The 62 grain and 75 grain Tulammo shot at or under 3.5 MOA, with the 75 grain turning in cool 3.0 MOA. Bear in mind also that this ammunition was fired from a warm gun with a fouled bore, using a budget scope mounted in cheap rings. The SCR had a free-floating barrel but its construction was otherwise unremarkable. |

We only tested Tulammo here, but we would be shocked if cheap, steel-cased ammunition from other brands performed much differently. When it comes to making ammo as cheaply as possible, every company has essentially the same tricks up their sleeve, so the product will be largely identical. |

The test rifle did not have any failures (such as misfeeds or jams) during the test.

Takeaway

The steel-cased Tulammo ammunition grouped around 3 MOA when loaded with bullets that were appropriate for the barrel's twist rate, and the less empirical but much more tantalizing flyer-corrected score showed groups that were remarkably close to 2 MOA. We consider 4 MOA to be about the minimum for a rifle to be worth shooting, since 4 MOA is sufficient to reliably hit a head-and-shoulders target out to several hundred meters. Given that this ammunition is about as cheap as it gets, and still shoots well under 4 MOA, we'd call that a satisfactory purchase. Still, we can't speak for everyone, and this article may be all that some shooters need to decide they want to to steer clear of the stuff. That's okay, too; agree or disagree, our goal was simply to provide some hard data.

Whatever ammunition you buy, pay attention to your barrel twist when stocking up on .223, especially if you're running a 1:7 twist barrel. 75 grain steel-cased ammo is a bit of a rare bird, but when you do find it, it's sold at standard steel-cased prices. 62 grain is more widely available and can get the job done, but its performance is empirically worse from a 1:7 twist barrel. Finally, the ubiquitous 55 grain is the worst choice for the 1:7 barrels that many ARs come with today.

There are other complaints about steel-cased ammunition, such as poor reliability and wear on the weapon's internals, but in our opinion there is enough research out there to prove that these concerns are largely needless hand-wringing. It's true that (cheap) steel-cased ammunition is a bit less reliable, and it does wear out your barrel faster, but for many shooters (us included) these trade-offs are well worth the lower price.

Happy shooting.

The steel-cased Tulammo ammunition grouped around 3 MOA when loaded with bullets that were appropriate for the barrel's twist rate, and the less empirical but much more tantalizing flyer-corrected score showed groups that were remarkably close to 2 MOA. We consider 4 MOA to be about the minimum for a rifle to be worth shooting, since 4 MOA is sufficient to reliably hit a head-and-shoulders target out to several hundred meters. Given that this ammunition is about as cheap as it gets, and still shoots well under 4 MOA, we'd call that a satisfactory purchase. Still, we can't speak for everyone, and this article may be all that some shooters need to decide they want to to steer clear of the stuff. That's okay, too; agree or disagree, our goal was simply to provide some hard data.

Whatever ammunition you buy, pay attention to your barrel twist when stocking up on .223, especially if you're running a 1:7 twist barrel. 75 grain steel-cased ammo is a bit of a rare bird, but when you do find it, it's sold at standard steel-cased prices. 62 grain is more widely available and can get the job done, but its performance is empirically worse from a 1:7 twist barrel. Finally, the ubiquitous 55 grain is the worst choice for the 1:7 barrels that many ARs come with today.

There are other complaints about steel-cased ammunition, such as poor reliability and wear on the weapon's internals, but in our opinion there is enough research out there to prove that these concerns are largely needless hand-wringing. It's true that (cheap) steel-cased ammunition is a bit less reliable, and it does wear out your barrel faster, but for many shooters (us included) these trade-offs are well worth the lower price.

Happy shooting.